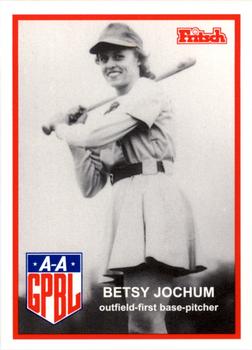

Betsy Jochum by Jim Sargent

Betsy Jochum was one of the sixty original players, as well as one of the best, in the early years of the All-American Girls Professional Base Ball League, a professional women’s circuit born during World War II and made famous in the 1992 movie A League of Their Own. Sixty years later, she had the pleasure of seeing her South Bend, Indiana, Blue Sox uniform travel around the nation as part of the Smithsonian Institute’s exhibit on “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.”

Betsy, one of South Bend’s fifteen players in the league’s inaugural 1943 season, was a Blue Sox standout through her final season of 1948, when the circuit grew to an all-time peak of ten teams. A right-handed batter, she averaged .246 in her career. Gifted with a keen eye, good reflexes, and a quick swing, she led all hitters in the second half of 1943, finishing with a .295 mark. She also led the league for all of 1944, averaging .296. In six seasons, “Sockum” Jochum, as fans often called her, connected for 43 doubles, 29 triples, and seven home runs. A good run producer, she often batted in the middle of the lineup, at least after her second year. Though mainly a singles hitter, she batted in 232 runs, averaging over 38 per season and produced a personal-best 63 RBIs in 1946.

Pleasant, attractive, and quiet, the 5-foot-7 brunette was fleet afoot, exciting players and fans alike with fine catches and strong throws from the outfield. During her professional career, she enjoyed a long string of highlights. Reflecting on her experiences at the AAGPBL Players Association Reunion in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, in 1997, Jochum said fans often gave players money for good hits or good defensive plays. For instance, Blue Sox rooter Arnold Bauer liked to give the women a silver dollar with their birth date on it for hitting a double, a triple, or a homer. Betsy remembered winning a wrist watch, an RCA radio, and a record player for outstanding games.

In 1944, Jochum produced her greatest overall season, leading all regulars with a .296 average. Considering the league was using underhand pitching and a softball with a 12-inch circumference, her “deadball” hitting mark was excellent. In fact, she led the league in several categories during 1944: most hits (128), most singles (120), and most stolen bases in one game (7) on August 2. Betsy batted lead-off or in the second spot much of the year and still produced 23 RBI. An exceptional all-around athlete, she had the speed to track down long fly balls, and she ran the bases well. Overall, she stole 358 bases, averaging 60 per year and peaking in 1944 with 127.

Showing her versatility, she also pitched in 1948, the first year the All-American League shifted to overhand hurling. The result: the right-hander posted a record of 14-13 and a 1.51 ERA in 215 innings, a good performance considering the Blue Sox finished third in the five-team Eastern Division with a losing record of 57-69. Still, despite six years of stellar performances, Betsy was traded after the 1948 season—but she refused the deal, and instead retired from pro ball.

Jochum was born in Cincinnati on February 8, 1921, to Frank and Katherine Jochum, German-speaking Hungarians who immigrated to America, landed at Ellis Island, and, eventually, arrived in Cincinnati in 1917. Along with her older brother Nicholas, or Nick, and her younger sister Frances, Jochum grew up in a working class family that reflected her parents’ newly-earned American values.

Jochum attended Hughes High School, where she participated in the only sports available to girls: after-school intramurals like basketball and softball. Betsy had outstanding athletic skills, including exceptional hand-eye coordination, quick reflexes, good speed, and a strong arm. She liked competing in Amateur Athletic Union track and field events such as the baseball throw. The Cincinnati native remembered one competition held in Connecticut in 1938 where her heave of 276 feet, short of Babe Didrikson’s 1930 record of 296 feet.

“I started playing fast-pitch softball when I was twelve or thirteen years old,” Jochum said in 1997. “I played for Vic Brown’s ‘Rosebuds,’ a florist from Covington, Kentucky, across the Ohio River. Later, my brother Nick and I got jobs with a packing company, H.H. Meyer. I played for their fast-pitch softball team, and we played in leagues in Cincinnati and in Covington. Two or three girls, Dorothy Kamenshek was one, played on the Meyer team and later played in our league.”

Like most other All-Americans, Jochum was still in high school when she started playing semipro ball: “Our Vic Brown team went to a national softball tournament in Chicago. The H.H. Meyer team went to the nationals in Detroit in 1940. We were one of the last four teams in the tournament when we finally lost. An Arizona team won it.”

Modest, bright, and talented, Jochum later attended business school and learned to operate the comptometer, a kind of calculating machine. She came of age during the Great Depression when jobs were hard to find. As a result of playing on the Meyer ball team, she and Nick got jobs at the packing house for a couple of years. Later, she found a job at the French Bauer Dairy doing comptometer work. In fact, Betsy was playing semipro ball and working for H.H. Meyer, earning $16 a week, when she signed a contract for $50 per week to become an original member of the All-American League. While playing for South Bend, Jochum resumed her comptometer job in Cincinnati during the off-season. After leaving baseball, she was hired to operate a comptometer at Bendix Home Appliances in South Bend. Finally, she saved enough money to attend college, graduating from Illinois State University in 1957 with a degree in Physical Education. She taught junior high PE in South Bend’s schools until retiring in 1983.

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1942 Major League team owners were informed by the Office of War Information that a huge manpower mobilization program was scheduled for the summer of 1943, and the mobilization could cause the baseball season to be postponed. Phil Wrigley, Chicago Cubs owner and creator of the All-American League, figured the best way to keep Wrigley Field open was to establish a good women’s pro circuit to attract baseball fans who might otherwise be lost to the major leagues for the duration of World War II. Even though the All-American later succeeded, Wrigley’s real love was his Chicago Cubs. After the 1944 season, with the war’s end in sight, he sold his interest in the girls’ league to his advertising chief, Arthur Meyerhoff.

On Saturday, April 18, 1943, Jochum was one of more than a dozen local female athletes invited to a special tryout at Cincinnati’s Turkey Ridge Field. Jack Sheehan, the Chicago Cubs’ head scout and organizer of several All-American tryouts across the Midwest, watched the young women hit, run, field, and slide under chilly conditions. That night he selected six, including Jochum, an outfielder, and Dorothy Kamenshek, an outfielder-first baseman who later starred with the Rockford, Illinois, Peaches.

Jochum, thrilled at the chance to play pro ball, signed and mailed back her contract. A few days later she received a notification letter from Ken Sells, president of the new league. Spring training would open at Chicago’s Wrigley Field on May 17, and another letter with more details would arrive: “It isn’t long now until May 17 and it would probably be a good idea for you to start getting into condition. It will make your training period that much easier.” Women like Jochum, then twenty-two, read about the All-American League in early March when newspapers such as the Cincinnati Enquirer ran a story explaining the “Girls’ League.” Ken Sells said the league hoped to profit from the “mistakes” of baseball, for example, by having women sign contracts modeled after those of the Actors Equity Association, meaning players had an option for renewal, but they were not bound to a team in perpetuity by a “reserve clause.”

On Sunday, May 16, when Jochum and other Cincinnati prospects rode the railroad streamliner James Whitcomb Riley to Chicago to register at the Belmont Hotel and prepare for tryouts, she reflected on her once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The Wrigley Field tryouts were dramatized in A League of Their Own, but the league began by using underhand pitching, not overhand. Still, if successful, the players were placed on the roster of one of the four fifteen-player teams. Besides the South Bend Blue Sox, the start-up league featured the Racine Belles, the Rockford Peaches, and the Kenosha Comets. The league controlled all players, and the girls were allocated to different clubs with the aim of keeping the teams balanced. Jochum joined fourteen other professional pioneers in South Bend.

Betsy, the Blue Sox, and the league enjoyed a good first year, as America continued to fight World War II. Patriotism was a main theme. Before each game, the girls formed a double line near home plate in “V” for victory fashion, and they joined in singing the national anthem. Programs, scorecards, and local merchants promoted war bonds. The admission price was under $1 for adults, kids paid less, and servicemen got in free. Also, teams left for a road trip following a night game, and games often ended between nine and ten o’clock. The players tried to sleep sitting upright on the day coaches of trains, arrived at the next city early in the morning, checked into a downtown hotel, slept a few hours, ate a meal, walked to the ballpark for practice, came back to the hotel for a break, and returned around six o’clock for games that started between 7:15 and 8:30 p.m. For personal and athletic adjustments, the girls relied on the team’s chaperone—in South Bend’s case, Rose Virginia Way, from Nashville, Tennessee. Miss Way, and other chaperones, counseled players, checked their housing, watched them on trips, served as part-time nurse to treat injuries, and became their friend. The league’s chaperones didn’t get much publicity, but they played a vital role for players living away from home, many for the first time. Further, chaperones also served as the players’ moral anchor, thus relieving the concerns of family and fans.

The circuit divided the season into a first half and a second half in 1943 and 1944, with the first-half winner facing the second-half winner in playoffs. First-half winner Racine beat Kenosha for the 1943 title, while South Bend took second place in both halves of the season with records of 28-26 and 30-24. In the end, injuries hurt teams playing 108 games from June through August, since the ball clubs usually played seven days a week, often with one or more double-headers, and used only fifteen players. For instance, near the end of the 1943 season’s first half, from Sunday, July 11, through Wednesday, July 14, the Blue Sox were forced to play four double-headers in four nights, caused in part by rainouts. The South Benders won the first game in each twin bill, losing both ends of the double-header only the last time—when the players were worn out.

Jochum, who was proficient at hitting line drives, long fly balls, and high bounders in the infield, played 101 games and led the league in at-bats with 439 and hits with 120. Averaging .273 for the year, but .295 in the second half, she topped everyone in singles (100) and doubles (12). She also contributed 27 walks, 66 stolen bases, seven triples, one home run, and 35 RBI. Rockford star Terrie Davis won the first half hitting title with a .372 average, but in the second half she ranked second to Jochum at .282. Racine led the league with a .236 team average, South Bend was second at .222, Kenosha third at .219, and Rockford last at .191. Incidentally, the relatively low batting averages from the 1943 season through 1947, before a smaller ball was introduced in 1948, reflect mainly the high quality of All-American League pitchers, who were recruited from across America and Canada, rather than a lack of skills by the hitters.

In May 1944, after the league’s spring camp at Peru, Illinois, and new player allocations, the Blue Sox roster featured a strong core of returning veterans. In addition to Jochum, South Bend returned the entire infield of first baseman Jo Hageman, of Chicago, second baseman Marge Stefani, from Detroit, third baseman-outfielder Lois Florreich, from Webster Grove, Missouri, and shortstop Dottie Schroeder, who grew up in Sadorus, Illinois. Also, both catchers, Mary “Bonnie” Baker, of Regina, Saskatchewan, and Lucella MacLean, from Lloydminster, Alberta, returned to the team along with the club’s top two hurlers—right-hander Margaret “Sunny” Berger, of Homestead, Florida, and lefty Doris “Dodie” Barr, from Winnipeg, Manitoba. Helen Moore became the chaperone.

New players allocated to the Sox included Lee Surkowski, an outfielder from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan; Charlotte Armstrong, a right-handed pitcher from Phoenix; infielder Rose Gacioch, from Wheeling, West Virginia; Ellen Ahrndt, a utility player from Racine, Wisconsin; and southpaw flychaser Vickie Panos, another Moose Jaw native.

In 1944, league officials made certain changes to the game on the field, such as reducing the ball’s size from 12 inches in circumference to 11.5 inches at midseason. Also, the length between bases was boosted from 65 feet to 68 feet at midseason, but the pitcher’s mound remained at 40 feet from home plate. Thus, when it came to underhand hurling and the dimensions of the diamond, the circuit mandated few changes for the second season.

Still, the friendly Jochum led the expanded six-team All-American League in hits with 128 and batting average with .296, while helping the Blue Sox challenge for the pennant. The second-half winner, the Milwaukee Chicks—an expansion club, along with the new Minneapolis Millerettes—defeated Kenosha for the championship. South Bend again finished runner-up in both halves of the season, posting records of 33-25 and 31-27.

Jochum produced a number of highlight games. For example, playing the Millerettes in Minneapolis on June 21, Betsy collected two of her team’s four hits off ace right-hander Dottie Wiltse, including the first home run ever hit by a woman at Nicollet Park. In a game characterized by outstanding defensive plays which the Blue Sox finally won, 8-7, one Minneapolis newspaper described her blast: “Other than the amazing antics of the fielders, the feature of the game was Betty [sic] Jochum’s home run in the seventh. This muscular young lady whaled one of Dottie’s best pitches far over Faye Dancer’s head in center field and it rolled almost to the flagpole. A fellow named Sweeney, one of South Bend’s rootingest rooters, gave her $25 for the smash.”

Commenting in 1997 on that 1944 game, Dottie (Wiltse) Collins said, “I never knew Betsy personally when we were playing ball. I have gotten to know her at reunions, and she’s a fine person. What I remember about her was, ‘Look out for the hitter in South Bend.’ She was a good hitter, one heck of a hitter!”

A few days later, the South Bend Tribune ran an article, “Jochum Takes Batting Lead with .323 Mark.” Jochum’s average ranked her first in the league, just ahead of teammate Dottie Schroeder, who slipped to .317 and into third place. Helen Callaghan of Minneapolis ranked second at .320, while South Bend’s Bonnie Baker was tied for third with Schroeder at .317. Later, on Monday, June 26, at Nicollet Park, Betsy hit her second homer of the season for South Bend’s only run. But the Millerettes won, 2-1, thanks to Wiltse’s seven-hitter and a pair of errors by Schroeder.

Players and fans continued to see daily reminders of the war. For example, inserted in the middle of the column for the South Bend Tribune’s story of the Blue Sox’s double-header split with the Millerettes on June 11, 1944, was the item, “Dorothy Maguire’s Husband is Killed.” Maguire, catcher for Milwaukee, learned from the War Department just before the Chicks played the Comets that her husband John had been “killed in action in Italy.” Despite the terrible news, Maguire played, but the Comets defeated the disheartened Chicks, 11-4. On July 13, in a positive note, the Tribune featured a picture of the Blue Sox girls buying war bonds at a desk manned by Leon Matthews of the American Trust Company. Each player pledged to buy a $25 war bond weekly. In early August, illustrating the community’s involvement with All-American teams, the Tribune ran a picture and a story highlighting South Bend’s Kreamo Bakers hosting a party for bakery employees and their many guests, including manager Bert Niehoff and the entire Blue Sox club. Afterward, Kreamo bought tickets for all guests to that night’s Blue Sox game.

On September 4, the 1944 season ended on a low note when South Bend split a season-ending double-header at Rockford, after dropping seven straight games. The Blue Sox broke their losing string behind Sunny Berger’s five-hitter, 2-0, but lost the second game, 3-0, as Dodie Barr yielded five singles, a double, a triple, and a homer, while Marge Stefani and Dottie Schroeder kicked in two errors apiece. The split gave South Bend a second half mark of 31-27, while Milwaukee led the second half with a 40-19 record. In the end, the Sox finished second in each half of the first two seasons, or as the Tribune said on September 6, “Always a Bridesmaid.”

The league’s final statistics showed Jochum ranked first in second half batting with a mark of .288. Betsy, who paced all batters with 59 hits, was trailed by Eleanor Dapkus of the Belles, who batted .269, while Merle Keagle of the Chicks was third with a .265 average. As an indicator of Betsy’s good hitting, the Blue Sox averaged just .174 as a team, ranking last in the six-team league. Regardless, South Bend’s directors announced the Sox were a financial success and would return for another season.

After the long Midwest winter and a league spring training camp in Chicago in May 1945, South Bend started the season with only six returning players from the 1944 club: Jochum, the left fielder, second baseman Marge Stefani, catcher Bonnie Baker, shortstop Dottie Schroeder, Lois Florreich, who played third base and center field, and right-hander Charlotte Armstrong. Marty McManus, a former major league second baseman and the manager of the Comets in 1944, replaced Bert Niehoff as the manager. Comely Lucille Moore became the chaperone.

South Bend’s ten new players, as pictured by the Tribune on May 22, 1945, were Elizabeth “Lib” Mahon, an infielder from Greenville, South Carolina; Kay Sopkovic, a catcher from Youngstown, Ohio; right-handed pitcher Nalda Bird, from Los Angeles; Gertrude “Lefty” Ganote, first baseman and utility player, from Louisville, Kentucky, who spent 1944 with Kenosha; Darlene Mickelsen, an outfielder who played for the Comets in 1944; Anne Surkowski, the outfielder from Moose Jaw whose younger sister Lee, also a flychaser, played for the Blue Sox in 1944; Dolores Klosowski, a southpaw hurler and first baseman from Detroit who played for the Chicks in 1944; and Betty Luna, a right-handed pitcher from Los Angeles.

Jochum, who appeared in 101 of the team’s 108 games in 1943 and 112 games in 1944, played all 110 games on the Blue Sox schedule in 1945. The league again used an 11.5 inch ball, the same as in the second half of 1944, and the length between bases remained at 68 feet, but the distance of the pitching mound from home plate was moved from 40 to 42 feet at midseason. Adjusting to the changes and to her new teammates and manager, Betsy’s hitting slipped to .237.

For the Blue Sox and Jochum, the 1945 season again turned into disappointment. South Bend started slowly, pitching became a problem, and injuries hurt the club. For example, the Blue Sox waived stalwart Doris Barr to the Racine Belles in early June. As Tribune sports editor Jim Costin reported on June 8, “She has a world of stuff, but has never had control during her stay here.” Two weeks later, on June 17, Nalda Bird pitched and defeated Alva Jo Fisher and the Rockford Peaches, 3-2, in a rain-slowed Sunday game. Charlotte Armstrong staged a pitcher’s duel with Rockford ace Carolyn Morris in the nightcap, but two eighth inning throwing errors by third baseman Lee Surkowski and three singles gave the Peaches three runs, and Morris, tossing a four-hitter, won, 3-0. On Monday night, however, the Blue Sox improved their record to 11-9 when Gertrude Ganote, a first baseman and outfielder, won her first game against the Peaches, 12-2. Canadian right-hander Olive Little, a star in 1943 who sat out the 1944 season to have her first child, suffered the loss, giving up 19 hits—including Jochum’s 4-for-5 night.

South Bend kept improving. On Friday, June 22, the Blue Sox took over first place with a double-header sweep of the Comets in Kenosha, twin wins that gave South Bend a sweep of the four-game set and extended Kenosha’s losing streak to nine. While Armstrong hurled and won the opener, 5-3, Bird, still limping, worked the second game and, despite the pain, tossed a four-hit shutout to win, 2-0. The Blue Sox kept playing more than .500 ball, highlighted by Bird’s 1-0 shutout of the Belles at Racine on July 7. Jochum fueled the win with two hits, the big one being a two-out RBI single in the seventh. In the bottom of the ninth, with two outs and Mary (Nesbitt) Crews aboard with a triple, Jochum made a “circus catch” near the foul line on Sophie Kurys’ long blast. Betsy’s catch sealed Bird’s five-hit victory.

As of July 8, the Blue Sox were leading the loop in batting with a mark of .222, topped by Lib Mahon at .298, hard-hitting Marge Stefani at .288, and Jochum at .246. Further, the roster changed with a four-player trade. South Bend sent Lois Florreich, batting .223, and Dottie Schroeder, hitting .179, to Kenosha in return for infielder Pauline “Pinky” Pirok (pronounced pie-rock), who was leading the league with 20 RBI, and infielder-pitcher Phyllis “Sugar” Koehn (rhymed with cane), who was second with 18 RBI. The changes didn’t help enough, as South Bend suffered injuries to Stefani (knee), Pirok (sprained ankle), and Mahon (knee), plus Betty Luna, the team’s top pitcher, was suspended for the remainder of the season in mid-July, after a dispute with Marty McManus, the no-nonsense pilot.

Partly as a result, the Blue Sox endured a nine-game losing streak on the road, capped by Bird’s 3-1 loss at Rockford on July 28. After winning three out of four against Fort Wayne, South Bend hit another nine-game losing skid. Armstrong snapped that slump with a brilliant four-hit 1-0 victory at Bendix Field over Grand Rapids. Most of the injured players had returned, and Jochum’s bat produced three of the home team’s ten hits. With the bases loaded in the bottom of the seventh via Bonnie Baker’s infield hit and bunt singles by Marge Stefani and Sugar Koehn, Jochum laced an RBI single off the hand of pitcher Jo Kabick. But the Sox stranded thirteen runners, and clutch hitting continued to be the team’s weakness.

South Bend’s fight for the playoffs came down to the final double-header against Rockford. On Sunday, September 2, Amy Applegren blanked the Blue Sox, 4-0, despite Koehn’s six-hitter. Sugar aided her cause with a double, but Pinky Pirok’s two singles were the team’s only other safeties. When the two clubs split a twin bill on Labor Day, the Blue Sox slipped to fifth place. In the Shaughnessy Playoffs, Rockford swept Grand Rapids in three straight, while Fort Wayne topped Racine in four games. The Peaches won the title, beating the Daisies in five games.

Hope springs eternal in baseball, and the Blue Sox ended the year by playing two exhibitions at Joannes Park in Green Bay with the Comets, the only other All-American club to miss the playoffs. Promoting the games on September 5, 1945, the Green Bay Press-Gazette reported, “Playing under rules virtually the same as regular baseball, the All-American Girls’ League has introduced to the sports-loving public a game that is entertaining, colorful and exciting. All of the league teams have been drawing big crowds this season, attesting to the popularity of the game.”

World War II ended when Japan surrendered officially on September 2, 1945, so the 1946 All-American season held the promise of playing in a peacetime era. Several changes occurred. While teams in wartime traveled mainly by the South Shore and North Shore Els (elevateds) out of Chicago, plus by day coaches in train rides to other cities, teams like the Blue Sox purchased a bus for trips. Also, the league expanded to eight teams, adding the Muskegon (Michigan) Lassies and the Peoria (Illinois) Redwings. The 112-game season would again be followed by the Shaughnessy Playoffs in order to determine the league’s champion. The All-American League grew in popularity, as league attendance reached a new high of 754,000. South Bend drew more than 120,000 fans, second only to Grand Rapids’ attendance of over 130,000.

In 1946 the league allowed each team to retain up to ten of the previous year’s players on a roster of eighteen. South Bend saw many talented newcomers, but the regulars who returned included Betsy Jochum, Sugar Koehn, Lib Mahon, Marge Stefani, Betty Luna (reinstated on May 20), Bonnie Baker, and Senaida “Shoo-Shoo” Wirth. In the last week of April, the league’s spring camp for 187 female athletes began at an old air base at Pascagoula, Mississippi. Following a week and a half of drills, the girls were allocated to the eight teams, and pairs of teams played eleven exhibitions en route to their home cities. South Bend teamed up with the Grand Rapids Chicks for one of four exhibition tours that allowed fans outside the Midwest to witness the All-American League in action and, therefore, help the league recruit new players.

The best rookie was Jean Faut, a third baseman who began pitching when the league allowed a sidearm delivery midway through the season. A native of East Greenville, Pennsylvania, the strong-armed right-hander kept improving as a pitcher and a hitter. Later, in 1951 and 1953, she was voted Player of the Year. Other new recruits included first baseman Inez Voyce, a lefty from Rathbun, Iowa; Joyce Hill, a catcher-first baseman from Kenosha, Wisconsin; Jenny Romatowski, a catcher from Wyandotte, Michigan; Daisy Junor, an outfielder from Regina, Saskatchewan; catcher Dorothy Naum, from Dearborn, Michigan; and Marie Kruckel, an outfielder-pitcher from the Bronx, New York. Chet Grant, former Notre Dame football star, coach, army officer, and minor leaguer became the pilot. Lucille Moore returned as chaperone.

Also, the league made more changes to the game on the field. Notably, the ball was reduced from 11.5 inches in circumference to 11 inches, the base paths were lengthened from 68 to 72 feet, and the pitching distance increased slightly, 42 to 43 feet, from home plate. But the biggest change came when pitchers were allowed to use a modified sidearm delivery, rather than just underhand, midway through the season. Clearly, the All-American League was moving more toward baseball with sidearm pitching. Still, this was a pitchers’ rather than a hitters’ league.

On Wednesday, May 22, South Bend got off to a winning start at Fort Wayne, defeating the Daisies, 6-5, in twelve innings. Third sacker Jean Faut paced the Blue Sox with four of her team’s thirteen hits, but she made two throwing errors, while Jochum, stationed in left field, rapped two singles and a double. Both scored twice, but catcher Dorothy Naum tallied the winning run in the twelfth on shortstop “Shoo-Shoo” Wirth’s infield roller. Southpaw Viola “Tommy” Thompson, the former Chick, scattered eight hits and won, while Dottie Wiltse, now married to Harvey Collins, a Fort Wayne resident and Navy veteran, suffered the loss. As of June 9, Shoo-Shoo Wirth led the league’s hitters with a .386 average. The Blue Sox led the loop with a team mark of .248, but Lib Mahon was the only other South Bend regular above .300. Lib paced the team with her .316 average, and Jochum was third at .287. The Blue Sox, however, ranked fifth of the league’s eight clubs with a 9-10 record, and Grand Rapids led the loop at 16-2.

South Bend spent much of the summer battling for second place in the All-American standings, but the Racine Belles, thanks to a big surge in August, led the league. The Blue Sox continued to improve, thanks to the development of many rookies, notably Faut, who posted a pitching mark of 8-3 (with one no-decision), once the league allowed the sidearm delivery. On June 20, South Bend, with Sugar Koehn on the mound and Lib Mahon knocking in three runs, defeated the visiting Peoria Redwings, 4-2, to claim second place. Jochum enjoyed a 2-for-4 outing, doubling in the first inning and scoring on Mahon’s first single. Betsy also tripled to center in the seventh, but she was stranded. The following night South Bend beat Peoria again, this time 17-8. Jochum led the potent offense with a single, a triple, and a home run, driving in five runs and scoring three more—to the delight of local fans.

Although the Hoosier squad stumbled to several losses in the season’s last full month, Jochum produced a four-hit night, scoring three runs and driving home a pair, to lead a 17-2 rout of Peoria at South Bend’s Playland Park on Saturday, August 10. The Blue Sox swept the four-game series, improving their season’s ledger to 56-35 with a 7-0 victory on Monday, a win based on Faut’s three-hitter and boosted by Wirth’s three hits and two by Jochum, who scored twice. South Bend kept a firm grip on third by defeating the Lassies in Muskegon on August 18. In that eleven-inning thriller, Jochum tripled in the last frame and scored on a sacrifice fly by Inez Voyce. When Jean Faut retired the Lassies, South Bend improved to 59-37, remaining two games behind the second place Chicks. Finally, on August 30, a crowd of 4,038 saw South Bend win a 4-3 squeaker over first place Racine to wrap up the home season at Playland. Jochum, always a team player, began the winning two-run rally in the ninth with a single. She stole second, and scored on Mahon’s single. With the bases loaded, Betty Luna, pinch-hitting for Daisy Junor, hit the season’s longest single to center, wrapping up the victory for Faut, who spaced five hits.

For Jochum the season ended in anticlimax. The Blue Sox lost the first game of a double-header with Racine when rookie Ruby Stevens, making only her third appearance on the mound, held South Bend to a pair of runs in seven innings, and Betty Russell, a reserve outfielder, singled home the winning two runs in the bottom of the seventh. By that time, Jochum, sliding into third base, had sprained her right ankle and was carried off the field on a stretcher. Dorothy Naum, a catcher, played right field in the nightcap, while Daisy Junor shifted to Jochum’s regular left field spot. For South Bend, the bad news was Betsy would miss the playoffs. Still, the Sox won the late game behind Tommy Thompson, 6-3, finishing the regular season one game out of second.

In the playoffs, Racine won the semifinal round in four games, eliminating the Blue Sox from the championship picture. For the 1946 season, South Bend led the circuit in team batting with a .220 mark, while finishing third in fielding with an average of .943. Dottie Kamenshek, Rockford’s sterling first baseman, led the league with a .316 average, but good-hitting Bonnie Baker tied Racine’s Sophie Kurys for second at .286. Jochum batted .250, making her third on her team and tenth in the loop for women playing 90 or more games. Also, Lib Mahon topped the league with 72 RBI, while Jochum placed second with 63. As a further indicator of her hitting prowess, Betsy, who batted 400 times, tied Kamenshek for the fewest strikeouts among regulars with ten.

The Midwest winter passed, spring beckoned, and the Blue Sox learned the All-American League would embark on a new adventure in 1947 by holding spring training camp in Havana, Cuba. In the last week of April, the circuit flew two hundred girls to Havana, and for many, like Jochum, the flight was their first airplane trip. The players spent a week and a half training and drilling before they were allocated to the eight clubs that played in 1946. According to the South Bend Tribune for May 3, 1947, the team’s roster included eleven players from last year: pitchers Jean Faut, Sugar Koehn, and Tommy Thompson; catchers Bonnie Baker and Dorothy Naum; second baseman Marge Stefani, shortstop Shoo-Shoo Wirth; third baseman Pinky Pirok; and Daisy Junor, Lib Mahon, and Jochum as flychasers. The Sox also acquired several rookies, including Marie “Red” Mahoney, an outfielder from Houston, Delores “Dolly” Brumfield, an infielder from Prichard, Alabama, and Jaynne Bittner, a right-hander from Lebanon, Pennsylvania. Feisty Chet Grant also returned as manager and Lucille Moore as the chaperone.

In 1947 the All-American game again changed on the diamond. While the league kept the 11-inch hardball, the 72-foot base paths, and the 43-foot pitching distance, the new rules permitted a full sidearm pitching delivery, partly because the limited sidearm experiment of 1946 proved too difficult to enforce. Still, many players who grew up hitting underhand hurling had problems adjusting to the new pitching style. South Bend was no exception, and Jochum, for example, saw her average slip to .211. Veteran Marge Stefani, however, topped the Blue Sox regulars with a .237 average, Jean Faut, who mainly pitched, hit .236, Lib Mahon, who suffered knee problems, fell to .234, Shoo-Shoo Wirth batted .227, and Bonnie Baker, who averaged .286 in 1946, dropped to .217. The Muskegon Lassies led the league with a team average of .223, while South Bend ranked fifth of eight teams with a .193 mark. Also, South Bend had the fourth best fielding mark of .948, while Grand Rapids led the loop at .964. The most important statistic was wins and losses. When the season ended, South Bend had a 57-54 record, finishing twelve games behind first place Muskegon (69-43). In fact, the Blue Sox fell from third place in 1946 to fourth in 1947, but the team’s record was good enough to make the playoffs for the second straight year.

After a rainout on Wednesday, May 21, the Blue Sox opened the season at Fort Wayne’s Memorial Park by defeating the Daisies, 3-1, behind Sugar Koehn’s five-hitter. Jochum, batting cleanup, paced the Sox with two hits. Baker, who singled once, scored all three runs—the third on Betsy’s bunt single in the eighth. The two teams split a twin bill, but the fourth game was rained out. Returning to Playland Park, the Blue Sox won three games against the Daises to take the league lead with a 5-1 mark. But rain played havoc with several games in early June, for example, halting a scoreless tie in the seventh inning at Playland against Rockford. On June 11, Faut, now the team’s pitching star with her excellent fastball and sharp curve, held visiting Kenosha to four hits, and her teammates scored in the ninth to win, 1-0. The Sox then slumped, losing ten of twelve games, capped on June 28 by Koehn’s 4-3 loss in Muskegon to the Lassies.

South Bend’s 1947 season continued in topsy-turvy fashion as, for example, the team often split double-headers. On July 21 in Grand Rapids, the Blue Sox won the opener behind Faut’s stellar two-hitter, 2-0, but the Chicks shelled Koehn for seven runs in the first inning of the nightcap to win, 9-1. The split left South Bend with a record of 29-31, two games behind fourth place Peoria. The remainder of the season proved to be a battle for fourth place, which the Blue Sox gained by splitting yet another twin bill, this one at home against Rockford on July 28. Jochum, batting third, paced the nine-hit attack in the first game with three safeties, including a triple, and she scored once. Ruth Williams won, 3-0, on a two-hitter. In the nightcap, Jochum and Baker singled while Mahon tripled, but Rockford’s Helen (Nicol) Fox won, 2-0, behind tight defense.

On August 4, South Bend continued the battle for fourth by beating the Comets in Kenosha, 4-2, thanks to Koehn’s four-hitter and two brilliant defensive plays by Jochum in left field. Betsy took away an extra base hit from Audrey Wagner by racing deep into left center to grab a long fly in the sixth, with the Sox ahead, 4-1, and the Sox star wheeled and fired to first base, doubling off the runner. In the ninth, Betsy made a shoestring catch off “Jerry” O’Hara’s low liner. Later, South Bend slipped, losing seven out of nine games, before defeating Racine at Playland twice, the second a 7-3 victory on August 26.

In the league’s playoffs, Grand Rapids defeated South Bend in five games. Also, Racine ousted Muskegon in four games, and the Chicks won the All-American League championship over the Belles. Following another offseason of living and working in Cincinnati, Betsy took a train to the league’s spring training camp at Opa-Locka, Florida, made the squad, and, touring with her Blue Sox teammates, played the return exhibition schedule with the Grand Rapids Chicks.

The 1948 season marked a historic turning point because the All-American League shifted to overhand pitching. Further changes made the game more like baseball, including reducing the ball’s size to 10 3/8 inches and lengthening the pitching distance from 43 feet to 50. The base paths remained at 72 feet, the 1946 length. Meanwhile, two of South Bend’s original 1943 players remained on the roster: Jochum and Bonnie Baker. Beginning in 1947, Dr. Harold Dailey, a tight-fisted dentist who likely understood less about baseball than the average fan, became the team’s president. In 1948, Dailey’s meddling with players and his false claim that Marty McManus, the manager, was drinking on the job, alienated McManus, a solid baseball man, and undermined his authority with the players—a problem that had plagued Chet Grant for two seasons.

Asked whether the changes in 1948 affected her hitting, Betsy, speaking in 2008, replied, “No, the rules changes didn’t really make much difference in hitting. I learned how to pitch, but I had a strong arm as an outfielder, so that wasn’t hard either.” A few weeks into the season, the veteran flychaser, who started the year slowly at the plate and ended up hitting a career-low .195 (still the fifth best mark on the team for those playing 100 or more games), was asked to pitch. Indeed, Jochum took the mound, learned the pitching fundamentals, and fashioned a 14-13 record. South Bend, however, remained short of good overhand hurlers. As a result, the Blue Sox finished third in the East Division with a 57-69 ledger, the club’s first losing record since 1945.

Statistics, however, hardly measure Jochum’s worth to her club. Known for her positive temperament, her steady hitting, and her classy fielding, the longtime Blue Sox star was an unselfish team player. “She was so good in the field,” Lib Mahon recalled in a 1997 interview, “that she always made the tough plays look easy. And she never claimed any credit for herself.”

In early August, Jim Costin wrote a neat column entitled, “Posies for Jochum.” The Tribune’s sports editor called her the team’s best all-around player: “It is the consensus of opinion among Blue Sox fans that the finest all-around job being done for the team this year is that turned in by Betsy Jochum, pitcher-outfielder-infielder. She is right near the top among the league’s pitchers with a record of 13 victories and six defeats, and she plays the outfield or infield with such marked ability that manager Marty McManus uses her quite frequently on the nights when she isn’t scheduled to pitch. What enhances her value to the team … [is] she’s never mad at anybody or anything, and has her eye at all times on the team’s success rather than on any personal glory. She wasn’t hitting very well at the start of the season, but in her last four trips to the plate in Playland Park she has hit a home run, a triple and two singles.”

The 1948 season opened with a three-game series at Playland Park against Peoria on May 9-11, and it ended with a double-header scheduled with the Springfield Sallies on September 6, a twin bill that was later moved to Playland. After splitting the final two games with Springfield, South Bend ranked third in the East behind Grand Rapids (77-47) and Muskegon (66-57). In the postseason, the Blue Sox met the first place Chicks in a best-of-five quarterfinal round of the Shaughnessy Playoffs. Jean Faut won the opener in 22 innings, 3-2, but Jochum lost the second game in 11 innings, 3-2, when “Millie” Earp hit an RBI single. Betsy didn’t play in game three when teammate “Lil” Faralla hurled a four-hitter and won, 2-1. The Cincinnati native also sat out game four, when Faut lost another extra-inning duel, 1-0, this time to Alice “Al” Haylett. Jochum started the final contest and lasted five innings, surrendering two runs on five hits. Faralla finished the game, but Earp twirled a one-hitter to whitewash South Bend, 3-0.

Regardless, Jochum performed so well that at the season’s end that Marty McManus encouraged her to ask for a raise. A few days later, she spoke with Doctor Dailey, South Bend’s president. Dailey, however, refused the raise, and, resenting players who wanted more money, decided to trade Jochum. He arranged a swap with Peoria, but announced the deal in a sleazy manner. Betsy was angry, partly because she first heard about it while eating lunch with several of her teammates, including Lib Mahon, Lil Faralla, and Sugar Koehn at Parkway Lanes, a bowling alley across the street from Playland Park. Dailey, she recalled in 2008, placed a call to the bowling alley and spoke with Mahon, who came back to the table and said, “A very good player has been traded.” The next day Betsy learned about the trade from a teammate, and she ultimately decided to retire. She had many good friends in South Bend, plus a comptometer job at Bendix. Despite her achievements on the diamond, Betsy’s fine career with the Sox ended on a low note.

The less-than-pleasant end to Jochum’s career was a scenario not unusual for longtime professional ballplayers. Betsy was an important member of the Blue Sox, and she has many lasting memories of her league years. For instance, people have asked if she remembered the time she caught a long fly ball barehanded. The Cincinnati native explained, rather modestly, “It was hit over my head to my right-hand side, so I couldn’t really get my glove on it. I was playing left field at Bendix Field in South Bend, but I don’t remember who we were playing.”

Jochum’s favorite memories include:

- The South Bend fans: “The same faithful fans would sit behind our dugout every night, and they would yell, ‘Sockum Jochum’ when I came up to bat!”

- The first All-Star game in mid-1943, played under temporary lights at Wrigley Field, between two teams composed of Blue Sox and Peaches players versus Comets and Belles players

- Taking the spring training trip to Havana, Cuba, in 1947: “I took my first airplane flight, we stayed at the Seville-Biltmore Hotel, and we played our games at the ‘Gran Stadium.’ All the teams were filmed for Fox News going down the steps at the University of Havana.”

- Enjoying a cruise across Lake Michigan from Muskegon to play a game in Wisconsin: “This was a special treat for us, and the driver took the bus around the lake.”

- Riding on the team’s private bus starting in 1946: “No more trains or luggage to carry!”

- Making her debut as a pitcher on May 29, 1948: “I gave up two singles, struck out five, walked none, and allowed only four runners on base.” Betsy won that first game, 6-0.

A valuable hitter, an excellent fielder, a solid run-producer, and a dedicated team player who was well liked by her teammates, by many opponents, and by South Bend’s loyal fans, Betsy Jochum represented both the ideal and the reality of Phil Wrigley’s enduring image of the feminine and graceful but highly skilled All-American baseball player.

Jochum died at the age of 104 on May 31, 2025.

Sources

The best sources of information about the All-American Girls professional Baseball league include the Players Association web site, hmttp://www.aagpbl.org/index.cf, the Northern Indiana Center for History, in South Bend, which holds the archives of the AAGPBL, and the Joyce Sports Research Collection at the University of Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Library, which has an excellent collection of AAGPBL materials. The South Bend Tribune has been invaluable for researching the Blue Sox, and I was able to use Betsy Jochum’s scrapbook covering the years 1943-1945 and 1947. Also, I interviewed several players, including Jochum (1997, 2008), Jean Faut (1995, 1997, 2007), Lib Mahon (1997, 1999), and Dottie (Wiltse) Collins (1997). Finally, the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York, has useful files on the AAGPBL, and the best book was written by Merrie Fidler, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006).

This article was written by Jim Sargent for the Society For American Baseball Research