Riley Gaines has become the darling of the far-right by using transphobia before science to make bank from attacking the community.

By Hope Pisoni, Uncloseted Media

This story was originally published in Uncloseted Media, an LGBTQ-focused investigative news outlet.

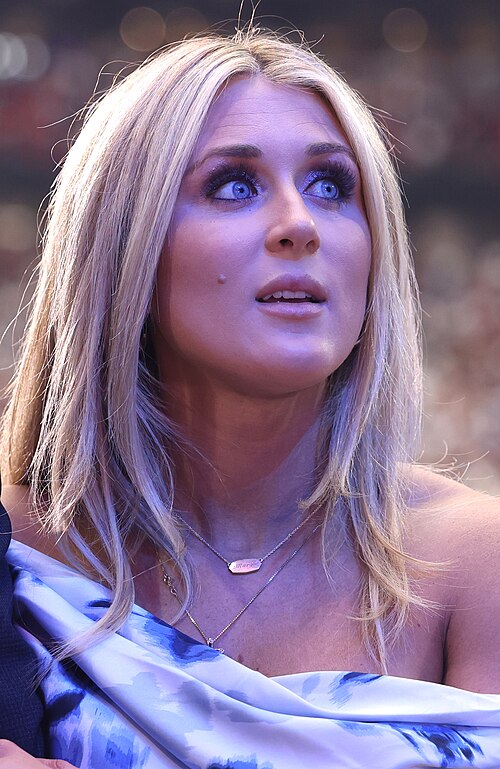

At the 2022 NCAA Division I Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships, Riley Gaines’ and Lia Thomas’ teammates cheered from the sidelines as they watched the 200-yard freestyle. Gaines, the team captain swimming for the University of Kentucky, and Thomas, swimming for the University of Pennsylvania, tied for fifth place, both finishing the race in just under one minute and 44 seconds.

“We were all standing there cheering for [Gaines] on the podium and she just looked so pissed off,” says one of Gaines’ former teammates. “I was looking at my teammate and I was like, ‘Dude, this is the worst thing that could have happened."

Thomas was fresh off of becoming the first trans athlete to earn an NCAA Division I title and had become the target of controversy throughout the season, with organizations like Save Women’s Sports and Concerned Women of America using her success as a rallying cry against trans women’s participation in sports. Gaines’ teammate, who asked to remain anonymous due to concerns about grad school applications, told Uncloseted Media that tensions had already been high prior to the competition but reached a boiling point when Gaines and Thomas tied.

“She, for months leading up to that, had this bias in her head, and I think that was the last straw that gave her the push to speak up about it,” says Gaines’ former teammate, adding that she could never have predicted that this would be the start of a lucrative career for her former captain.

Less than a week after the race, Gaines began skyrocketing to right-wing fame when she was profiled in an article by right-wing commentary website The Daily Wire, where she criticized the NCAA for awarding Thomas a trophy before her.

“The more I thought about it, the more it fired me up,” Gaines told the conservative media outlet founded by Ben Shapiro.

The next month, she would testify before the Kentucky senate in support of a bill that would ban trans women from women’s sports. By May 2023, she had appeared on Fox News 29 times and been hired as an official spokesperson for the Independent Women’s Forum (IWF), a far-right organization known for anti-trans activism.

Since the infamous race against Thomas, she’s sued the NCAA, headlined nationwide speaking tours and launched the Riley Gaines Center at the Leadership Institute. This month, Gaines appeared at the signing of Donald Trump’s executive order banning trans women from women’s sports, where he personally congratulated her for her activism and for being “at the forefront” of the issue.

As Gaines’ star has risen, her former teammate says it’s become too much to stomach. “I haven’t followed her, and I’ve tried to distance myself from it,” she says. “It’s just been insane how she has changed this narrative … into ‘trans people shouldn’t compete in sports."

Gaines’ meteoric rise reflects a strategy that far-right groups, including the anti-LGBTQ hate group Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), use to prop up young, primarily white, cisgender women and girls as figureheads in their movement to ban trans girls and women from sports.

While research surrounding trans women in sports is ongoing, Gaines and other right-wingers rarely cite it when pushing for laws that rollback trans rights. Instead, their rhetoric is fueled by transphobia and fearmongering about how trans girls and women are jeopardizing the safety of cis females.

This strategy seems to be working. Since 2020, 27 out of 50 states have banned trans students from competing on teams matching their gender identity.

“There’s a whole right-wing media machinery and money that started strategically using people like Riley Gaines to make these arguments around Title IX and [the idea] that trans athletes are ‘destroying’ women’s sports,” says Mia Fischer, a professor of communications and women & gender studies at University of Colorado Denver. “Anti-trans activism has made sports a key issue, and they’ve very effectively used it as a trojan horse to attack other trans rights.”

How sports became a target

Openly trans athletes are exceedingly rare, with fewer than ten competing in the NCAA, according to the association’s president. Despite this, leaked emails show that, as early as 2014, ADF was coordinating with the American College of Pediatricians—another anti-LGBTQ hate group—to produce pseudoscientific studies.

In one email, ADF requests a report that “make[s] the point that interpreting Title IX to include protections for ‘gender identity’ will harm girls by allowing boys to displace girls on competitive sports teams.” This argument would form the backbone of their legal and rhetorical strategy for pushing trans sports bans.

Multiple trans athletes told Uncloseted Media that their presence in sports was, for a long time, mostly irrelevant. But Fischer says that began to change in 2017 when two Connecticut trans girls drew controversy after multiple first- and second-place wins in the state’s high school track competitions, and some parents raised concerns about fairness.

ADF—a group that has advocated for conversion therapy and against marriage equality—jumped on this opportunity and helped the families of three cisgender Connecticut runners file a lawsuit in 2020, arguing that allowing trans girls to compete on girls’ sports teams violates Title IX. The plaintiffs in the ongoing lawsuit were quickly promoted by ADF and allied groups.

As with Gaines, they testified in favor of other states’ anti-trans legislation, published op-eds and appeared on Fox News. One plaintiff’s mother, who started a petition to change Connecticut’s policies around trans athletes, was featured on a panel with the Heritage Foundation—the organization that penned Project 2025—to discuss the importance of banning trans women from sports.

“That was a really scary time,” says Andraya Yearwood, one of the trans runners from Connecticut, adding that she received sustained harassment both online and from some parents. However, she said most teammates and competitors were supportive. “I knew people didn’t want me to run, but I didn’t know that it would reach such heights.”

Yearwood remembers online strangers telling her to quit running, calling her a cheater and sending her posts and videos that misgender her and call for her to be banned from her sport. At one track meet, she recalls hearing cheers from the crowd after she was removed from a race for a false start, and she says one woman verbally accosted her.

“I just stood there for a few seconds. I didn’t say anything,” Yearwood told Uncloseted Media. “I was too stunned to speak. Then I turned around and I kept walking. I just was like, ‘I’m not gonna pay you any mind. I have better things to worry about, like my race.’”

Riley Gaines’ rise to stardom

As ADF’s lawsuit moved through the courts, Gaines’ star rose. She successfully lobbied local governments for sports bans, was featured in campaign ads for Rand Paul and Ron DeSantis and landed a podcast called “Gaines for Girls” on Fox Nation. She also worked with International Chess Federation leadership to ensure trans women would be banned from their women’s events.

Gaines’ rhetoric wasn’t always so extreme. In her initial appearance in The Daily Wire, she consistently genders Lia Thomas correctly.

“I am in full support of her and full support of her transition and her swimming career,” Gaines told The Daily Wire, “because there’s no doubt that she works hard too, but she’s just abiding by the rules that the NCAA put in place, and that’s the issue.”

But as the far-right rewarded her, Gaines’ rhetoric became increasingly fueled by transphobia. Today, she misgenders trans people and laments watching Thomas “steal trophies from girls I’d known my whole life.”

“Lia Thomas is not a brave, courageous woman who EARNED a national title. He is an arrogant, cheat who STOLE a national title from a hardworking, deserving woman,” she tweeted in March 2023, almost exactly a year after her tying match.

This switch-up is not unique. Yearwood says prior to the Connecticut lawsuit, she had been friendly with Chelsea Mitchell, one of the plaintiffs. Weeks before the lawsuit was filed, Mitchell congratulated Yearwood in an Instagram message shared with Uncloseted Media.

“That really shocked me,” Yearwood says. “ [It] was a bit confusing.”

Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.

“People become more ideologically indoctrinated,” says Fischer. “The influence of various anti-LGBTQ Christian conservative groups on these athletes becomes really clear, in that their views become more narrow, exclusionary, or even radical fundamentalist.”

There’s also a financial incentive for Gaines to lean into this rhetoric. Gaines was paid nearly $12,000 by Ron DeSantis’ presidential campaign in 2023, and her center was awarded $20,000 for collaborating on a “Real Women of America” pinup calendar with Conservative Dad’s Ultra Right Beer—which the founders describe as an “anti-woke” beer company.

Gaines has also participated in paid speaking engagements at over 50 college campuses, landed two separate book deals and has her own merch collection with the Leadership Institute, with “Save Women’s Sports” and “BOYcott” t-shirts selling for as much as $40.

“She’s developing her stance according to who’s supporting her,” says Gaines’ former teammate. “With her sponsorships and with the big people commenting saying ‘you’re doing great things,’ I think it was inevitable that it would have led to that.”

On Fox News, Gaines has even gone so far as to bully and misgender kids, referring to an eighth-grade trans girl as a “mediocre man.”

Later in 2022, Gaines became an official spokeswoman for the IWF, an organization founded in the 1990s by a group of conservative women who were working to defend then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas from allegations that he had persistently sexually harassed a former advisor. Over time, they grew into a broader conservative women’s group with the help of significant funding from right-wing donors. Recently, their primary focus has been anti-trans advocacy.

IWF is part of the Our Bodies, Our Sports coalition, a collection of organizations that sponsors Gaines’ “Take Back Title IX” college campus tours, where she gives speeches advocating against trans women in sports.

In one speech at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Gaines said that calling for trans women to be banned from women’s sports is “how anyone with any amount of brain activity would probably comprehend this information.”

The Leadership Institute and manipulating the narrative

In August 2023, Gaines launched the Riley Gaines Center at the Leadership Institute with the goal of “protecting women’s sports.” The Leadership Institute, a member of Project 2025’s advisory board and funded by the Charles Koch Foundation, is known for training conservatives to be effective activists and politicians. Notable alumni include Mitch McConnell and Mike Pence.

Last summer, the center launched an online training, where Gaines details how to use Title IX to “Defend Women’s Sports and Stand Against Gender Ideology.”

“Biological sex has been replaced in favor of transgenderism,” Gaines says in the video. “[People are] being silenced for believing in the biological reality that there are only two sexes.” Subsequent videos instruct viewers how Title IX can be used to “silence” or “censor” students who engage in harmful rhetoric, like misgendering or deadnaming trans folks, and how students can instead use it to push back against this “censorship.”

The center also has a roster of young female ambassadors who, like Gaines, have become influencers of the anti-trans movement. Among them are members of the Roanoke College Swim Team, who made headlines when they claimed they were pressured to accept a trans woman on their team. However, the College’s administration released a statement stating that the trans woman in question never joined the team and withdrew her request after receiving backlash.

Despite this, the team appeared on stage at one of Donald Trump’s final 2024 election campaign rallies, where the president praised them for their protest. “The brave members of the swim team stood up to the transgender fanatics,” Trump said.

Gaines herself also claims on her center’s website that she was forced to share a locker room with Thomas. “We weren’t even forewarned that we would be forced to undress in front of a 6’4” fully intact, 22-year-old male. As if that weren’t enough, we were effectively silenced by our universities with threats and intimidation.”

But Gaines’ former teammate says this is untrue. “NCAA gave us a heads-up that all the locker rooms were going to be gender-neutral, and there were three locker rooms that we could have used … So Riley’s villainizing Lia with ‘I was changing in the locker room when Lia walked in and stripped down,’ and I’m like, ‘Riley, we knew this was a possibility.’ Riley shaped the narrative in her way.”

Uncloseted Media reached out to Gaines via the Riley Gaines Center with an interview request and a list of questions but received no response.

Cherrypicking White cis women

“There’s clearly a lot of media training that these people have received,” says Fischer, noting that the right-wing’s selection of white, traditionally feminine girls and young women is likely intentional. “If we think about traditional gender norms, they fulfill all these signifiers that we traditionally associate with feminine white athletes. I think this is also why media then attaches to certain people easier than to others and is able to create this celebrity status around them.”

Yearwood believes that anti-Black racism was an underlying element to the backlash she received, with many attacking her by playing on existing stereotypes of Black women as more masculine in contrast to their white counterparts.

“Because a lot of black women in general are often hyper-masculinized in American culture, I think that also contributes to the scrutiny that we faced in high school,” says Yearwood. “They had really focused on our muscle definition as we were running, and some of the comments were comparing us to other famous black athletes like Lebron James."

Yearwood says most of the hate she has received has been from older people. She believes that is why there’s so much focus by the right wing to find people like Gaines who can persuade younger generations to oppose trans women competing in sports.

“It’s funny when grown adults target teenagers, so I don’t think that would gain as much traction,” says Yearwood.

As Gaines’ star continues to rise, Trump’s recent executive women's sports, order, which empowers federal agencies to enforce a trans-exclusionary definition of Title IX in any institution that receives federal funding, can now deny trans athletes all over the country the opportunity to compete in sports.

For Yearwood, the hate from the anti-trans movement and from influencers like Gaines was so intense that she chose not to continue running competitively in college.

“I spent months going back and forth about whether I wanted to do track, and after making the decision not to, it did feel like I was losing a part of me,” says Yearwood. “There’s still times that I do wish I could still run track, and still have that kind of camaraderie on a team.”

The 19th News(letter)

News that represents you, in your inbox every weekday.

INFORM YOURSELF ABOUT THE ISSUES!

INSPIRE YOURSELF TO BE AN ACTIVE CITIZEN

AND PROTECTOR OF OUR DEMOCRACY!